How to ship hardware and software

Hardware wants certainty and predictability (at high quality). Software wants iteration speed and flexibility. I have worked at multiple companies (Shapeways, Oculus) that require tight integration between hardware and software. The release process is where the different approach to shipping comes crashing together (typically at the expense of users).

I remember walking into my first release planning meeting to talk about making a major update to a factory workflow that involved a new consumer-facing feature that would ship alongside a change in how we process 3D objects in the factory. I (naively) argued for an hour that we could take the same approach with hardware as we do with software. Surely we could just patch/hotfix any issues we experience in the factory. I couldn’t understand why we couldn’t just ship regularly (e.g. continuous deployment) to the factory and website simultaneously. It was all software, right? So why was everyone giving me blank stares...

Finally someone on the ops team spoke up: “We have to move printers, tables, and conveyer belts around the factory. We have to onboard new machines. We have to train people. How do we continously deploy all that?”

🤦🏼♂️ Hardware is hard.

Since then I’ve spent a ton of time thinking about how to help software and hardware teams work together. I’ll focus on the release process for this post because it’s typically the most contentious moment between teams.

The differences between software and hardware

A tension exists between software and hardware because of the physics involved. Software moves bits, hardware moves atoms. The time it takes to deploy software can be near-instantaneous whereas hardware has to move around the world at a pace much slower than the speed of light. A hotfix can be rolled back from 1,000 servers with the push of a button, but many hardware systems are still patched with a usb cable and a laptop, a usb drive, or worse. You get the picture. As a result:

Software teams optimize for iteration speed. They move quickly, have flexible deadlines, and avoid predicting what goes into each release as much as possible.

Software Teams tend to...

- Ship to learn

- Scope releases into tiny chunks

- Patch and rollback regularly

- Support few platforms (e.g. iphone/android or browser)

- Read more: Lean Startup methodology

Software teams consistently try to reduce the time it takes from idea→implement→feedback. Teams typically aim for a cadence of at most a week and often times try to approach ‘continuous deployment’ where they can release every few minutes (or whenever a chunk of code is ready to ship).

Hardware teams optimize for predictability. They move slowly, have rigid deadlines (and requirements), and need to know exactly what goes into each release.

Hardware Teams tend to...

- Have many dependencies (e.g. vendors, manufacturing)

- Plan releases far out in advance (sometimes years)

- Only hotfix if absolutely necessary

- Support many platforms or specific legacy tech

- Read more: Kaizen for software developers

Hardware teams also want to reduce the time it takes from idea→implement→feedback but they have physical constraints. As such, they tend to gravitate towards fewer releases, often shipping patches every month or every few months.

How do we ease the tension?

I’ve found three options to help hardware and software teams release software together. There is no perfect solution, but these seem to be the common permutations:

- Follow software cadence (Hardware suffers)

- Follow hardware cadence (Software suffers)

- Find a compromise that tries to met in the middle (These are complicated)

I am a strong advocate of the 3rd choice which is to find a compromise. I’ve seen hardware teams ship terribly buggy and problematic releases trying to follow a software model and software teams slow to a crawl trying to adhere to a rigorous hardware planning process.

Here’s what actually works

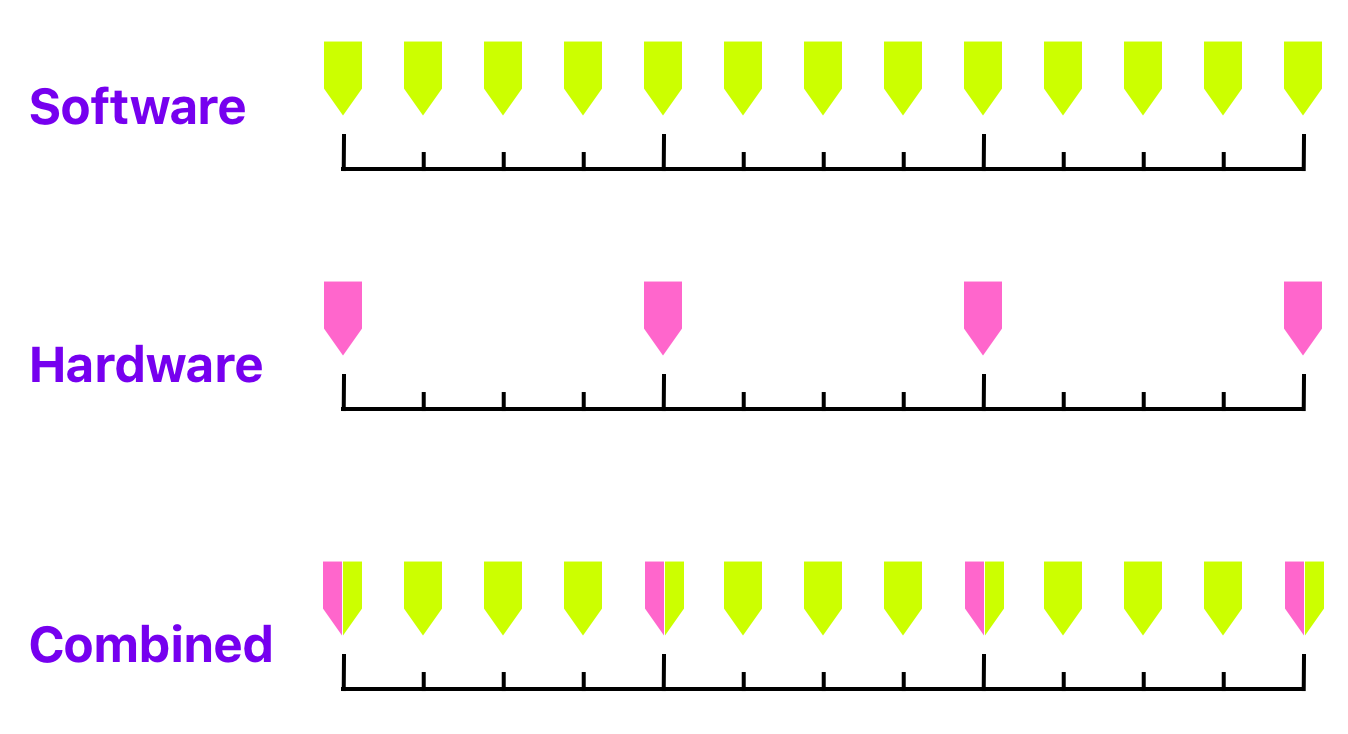

- Put software on a regular 'release train (e.g. weekly). What’s in the build rolls out the door. If you miss the train, you wait until next week.

- Put hardware on a fixed, predictable cadence (e.g. monthly or quarterly). Plan these releases with the rigor needed for your hardware team.

- Identify dates where the train overlaps the hardware cadence. These are your integration milestones. For these releases, software must plan rigorously and ensure any hardware-centric releases land during this time.

This model decouples MOST software and hardware releases. 80-90% of the time, the software teams have freedom to move fast and break things (or whatever your preferred slogan is). Hardware teams can plan rigorously and have a predictable schedule. The joint releases act as a contract where the software teams flex a bit to meet the requirements of the hardware teams. Because it only happens every once in a while, the planning overhead for software isn’t too heavy and teams typically don’t mind dealing with it.

Nintendo had to deal with hardware/software releases back in the day with ROB.

I’ve had alot of success running this model. Here are a few traps I see teams fall into when trying to implement it:

- Software teams need to account for hardware process dependencies. If you are making major changes during the integration milestone, you need to pre-write training material (if people’s jobs or a hardware assembly line are affected), help desk material (if end users will get stuck), or time to burn new builds onto the device before it leaves the factory.

- Plan your branching strategy in advance. Poor branching strategies make the integration milestone really messy. One especially tricky moment is when you miss the release train right before an integration milestone. You should map out this scenario in advance. Do you just punt on those changes until after the integration milestone? Pick them in? These things should be decided in advance, otherwise you’re in for some long nights.

- Name your milestones. These could be versions, letters, hurricane names, etc. You’ll often have two teams referring to these regularly and just using dates will get very confusing (especially if a release slips or hardware needs to move the milestone).

- Plan your rollback strategy. In software, it’s fairly easy to roll back a release. In hardware, you sometimes have releases you can’t rollback, or you have a heavy dependency chain that’s hard to work around. Like branching, you need to plan for rollbacks in advance and have a contingency plan that your oncall can execute for software, firmware rollbacks, or both.

- Anticipate software update/adoption rate - It’s common in software to wait until a percentage (e.g. 95%) of users have received your latest update to enable everything you’ve shipped in that release. With hardware, the math gets more complicated. Some users might not have devices plugged in or turned on for weeks. Often you need to gate software features on firmware updates (and likely support very old firmware versions). Be thoughtful about versioning and plan your update strategy at the same time you plan the milestone. You might need to punt certain features to the next release if your users are slow to update or invest in autoupdate or backwards compatibility.

If you want to read more about the intersection between hardware and software, I recommend The Phoenix Project and Albert Wenger’s excellent series on Kaizen for Developers.

Do you have advice for working on a hardware/software project? I’d love to hear it: @bdickason

Get my newsletter. It features simple improvements you can make to improve your day-to-day PM life. From Product Vision/Strategy to Goals and Metrics to Roadmaps and everything in between.

Post last updated: Jan 21, 2021

Posts

-

Take a break May 7, 2021

-

Make it cheap to fail Apr 30, 2021

-

Scarcity = Value Apr 23, 2021

-

Tools are a distraction Apr 16, 2021

-

Strength-Based Teams Apr 9, 2021

-

Small teams win Apr 2, 2021

-

Don't set vision, set direction. Mar 19, 2021

-

Do one thing well Mar 12, 2021

-

Take charge of your promotion Mar 5, 2021

-

Speed is the killer feature Feb 25, 2021

-

How to manage your manager Feb 19, 2021

-

Social thinkers vs. Solo thinkers Feb 11, 2021

-

Stop Writing and start Editing Feb 4, 2021

-

How to make time for strategic thinking Jan 28, 2021

-

How to ship hardware and software Jan 21, 2021

-

Use your damn product Jan 15, 2021

-

The 5 best Product books and posts Jan 8, 2021

-

Gather great feedback from your power users Jan 4, 2021

-

How to spend more time doing work you love Dec 27, 2020

-

Stop wasting time on strategy decks Dec 21, 2020

-

Less chat more writing Dec 2, 2020

-

How to lead strategic discussions Nov 19, 2020